Uveitis Case #2

Authors: Kevin Ly (1), Dr. Alex Kaplan (2)

Affiliations: (1) University of Alberta (2) University of Toronto

ID: 34M - blurred vision, headache, and tinnitus over the past 10 days.

Past Ocular History:

Myopia (-3.00 OU)

Recurrent allergic conjunctivitis.

No ocular surgery, no ocular trauma.

Ocular gtts: None

Relevant Medical History:

Hypertension

Recent URTI - 3 weeks ago, resolved.

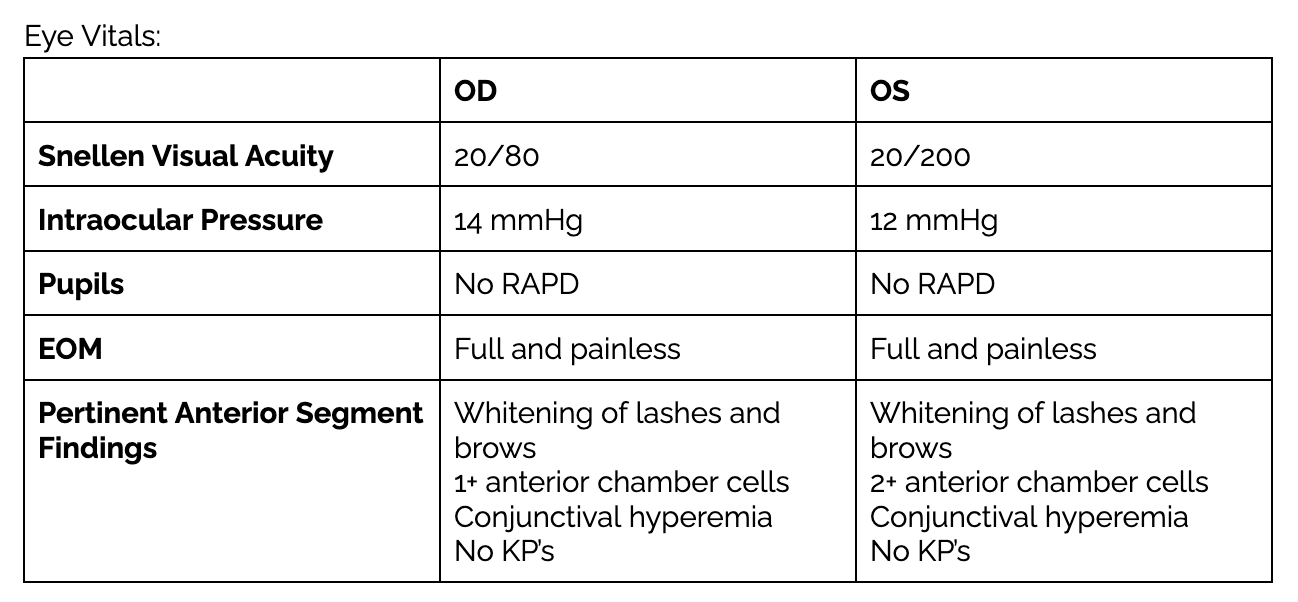

IVFA Transit: Right Eye

-

IVFAs OD at 21 seconds

Mid Arteriovenous Phase with Laminar Flow.

Key Features:

Early hypo-fluorescence seen most prominently temporal to the macula. Notice multiple dark spots masking the underlying choroidal fluorescence secondary to active choroiditis (1)

-

IVFAs OD at 49 seconds

Late Arteriovenous Phase.

Key Features:

Multifocal pinpoint hyperfluorescent spots concentrated in the posterior pole surrounding the optic nerve and macula OU - “starry-sky” appearance (1,3).

Hypofluoresence in the macular region from subretinal and intra-retinal fluid (2)

-

IVFAs OS at 53 seconds

Late Arteriovenous Phase.

Key Features:

Multifocal pinpoint hyperfluorescent spots concentrated in the posterior pole surrounding the optic nerve and macula OU - “starry-sky” appearance (1).

Peri-foveal hyperfluoresence secondary to pooling. The dye has entered the fluid filled cavities (2).

-

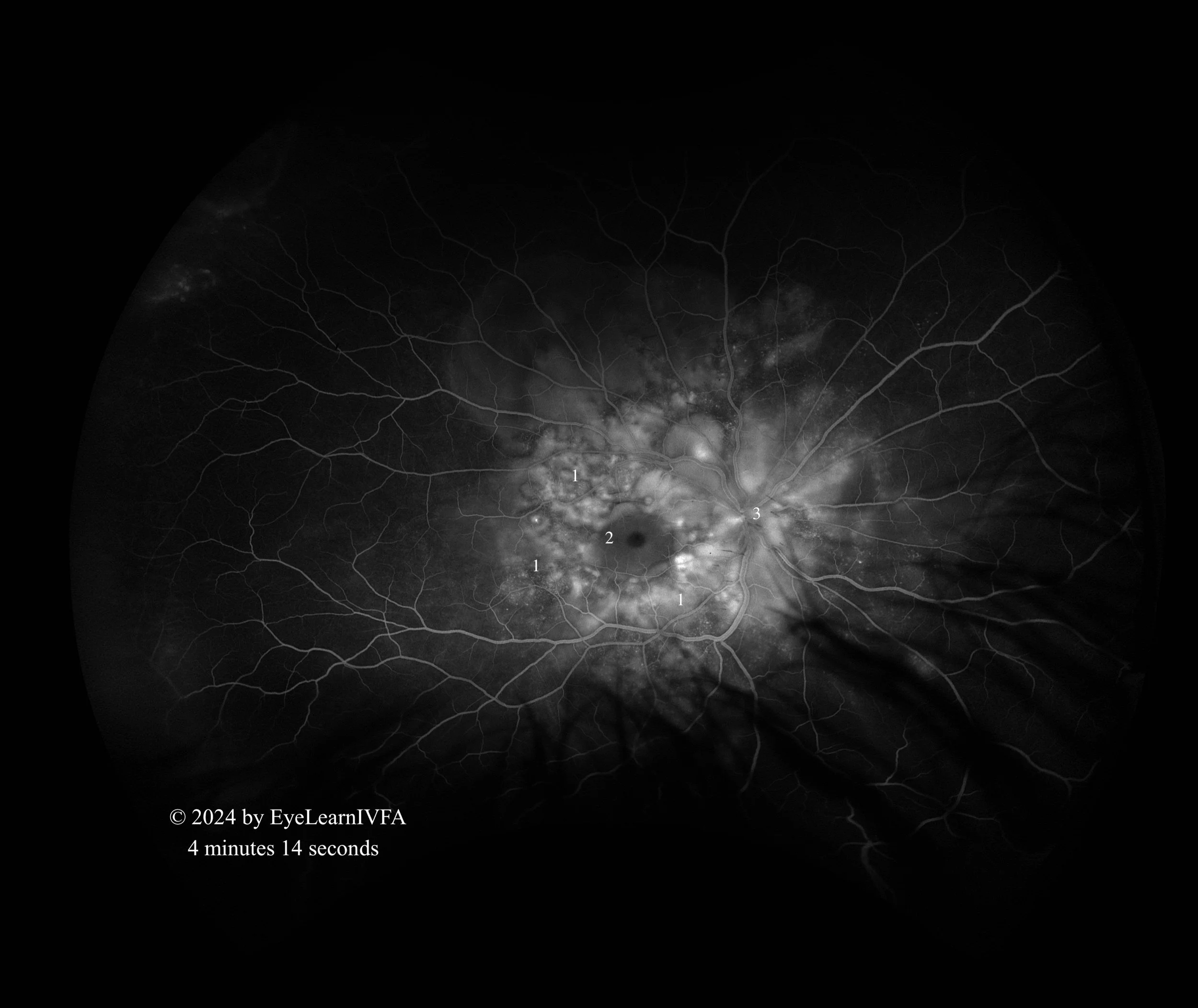

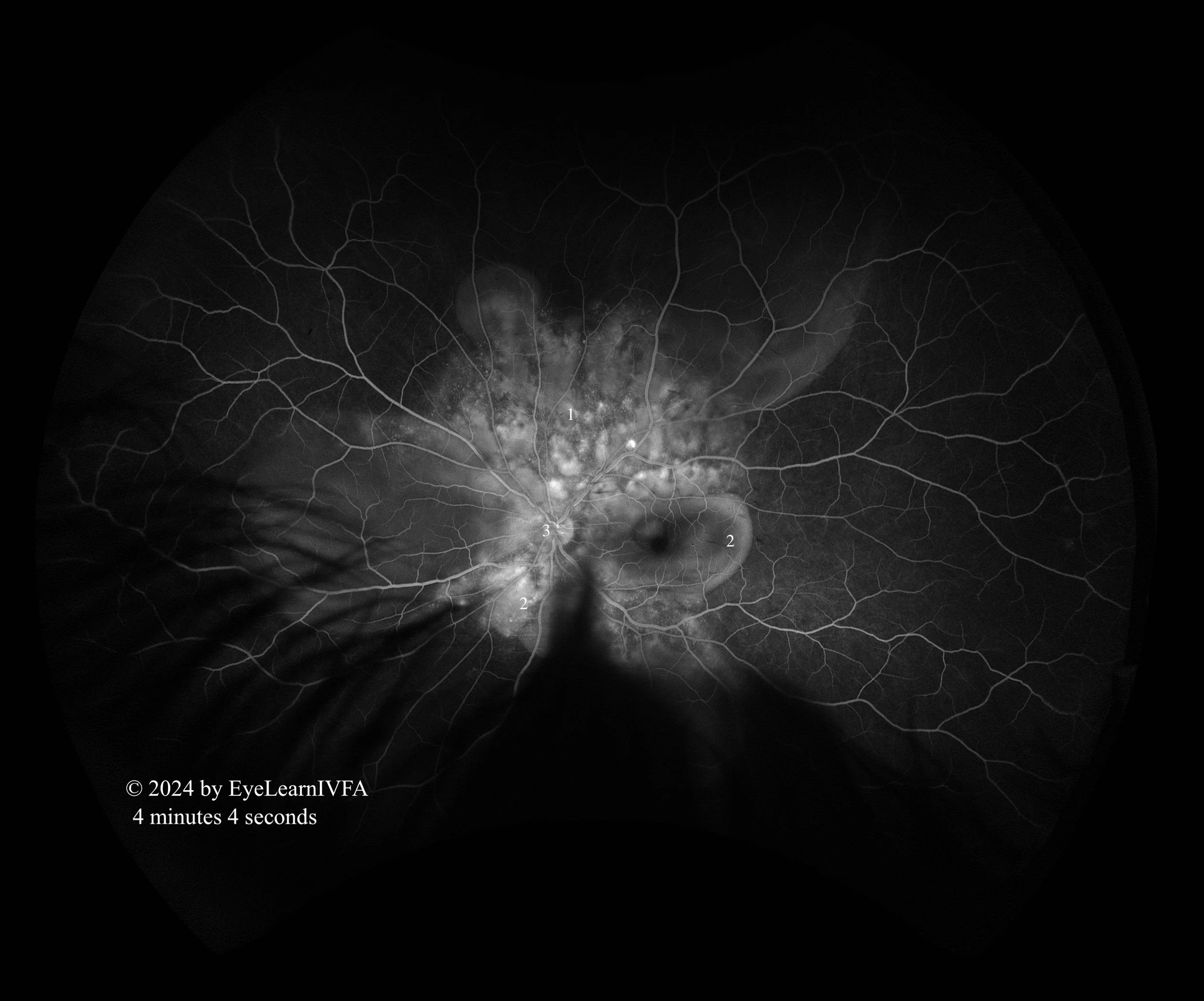

IVFAs after 4 minutes in both eyes

Late Phase.

Key Features:

Continued pattern of pinpoint areas of hyperfluoresence around nerve and macula - more obvious “starry sky” appearance (1)

The left eye shows pooling of dye resulting in hyperfluorescence (2), with the central macula being hypofluorescent.

In the right eye, there is hypofluorescence over the macula secondary to serous subretinal fluid (2).

Presence of hyperfluorescent optic nerve OS, with a ring of hypofluorescence (3).

-

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) is an autoimmune condition affecting melanocytes in the uvea, skin, ears, and meninges. Individuals with more pigmentation are at risk, including Hispanics, Asians, and Indigenous communities. Bilateral intraocular inflammation accompanied by neurological (headache), auditory (tinnitus), and integumentary (poliosis) findings describe the characteristic presentation of VKH - often diagnosed clinically. Evidence of subretinal fluid accumulation on OCT, and multiple pinpoint leakages and disc hyperfluorescence in a starry-sky on IVFA, supports the diagnosis of VKH. Importantly, a careful history should be taken to ensure no ocular trauma or surgery preceded the onset of uveitis, as this may indicate another disease process like sympathetic ophthalmia.

-

Sympathetic ophthalmia

Posterior scleritis

Uveal effusion syndrome

Central serous chorioretinopathy

Sarcoidosis

Hypertensive retinopathy

Syphilis

Tuberculosis

Neoplastic mimickers

-

VKH can present with a wide array of IVFA patterns, including spotted choroidal and optic disc hyperfluorescence, subretinal pooling of dye, and multiloculated subretinal pooling of dye. Because it is primarily a choroiditis, these features are not visible on fundus examination. Although the diagnosis is often clinical, IVFA is a useful tool for confirming diagnosis, monitoring progression, and ruling out other diseases on the differential diagnosis.

Further, there is bilateral bacillary retinal detachment evident on OCT. IVFA can distinguish VKH from other causes of subretinal fluid, such as CSCR, to guide appropriate management. In contrast to VKH, CSCR is characterized by inkblot or smokestack leakage and absence of vitritis, AC cell and optic disc hyperfluorescence. Posterior scleritis and sympathetic ophthalmia look similar, but posterior scleritis will usually have additional features like intense optic disc leakage and choroidal folds.

It is important to differentiate the two because the treatment of VKH (systemic steroids) may exacerbate CSCR. Lastly, IVFA can aid in recognizing complications (e.g. neovascularization) and differentiating acute-onset and chronic VKH, which will impact treatment decisions.

-

Rosenbaum JT, Sibley CH, Lin P. Retinal vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016 May;28(3):228–35. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000271.

Agarwal A, Rübsam A, zur Bonsen L, Pichi F, Neri P, Pleyer U. A Comprehensive Update on Retinal Vasculitis: Etiologies, Manifestations and Treatments. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022 Apr 30;11(9):2525. doi:10.3390/jcm11092525.

1.Arora A, Agarwal M, Chieh Loh N, Amin H, Menia NK, Agrawal R, et al. Diagnostic Workup of Retinal Vasculitis: An Algorithmic Approach. Ophthalmologica. 2024 Sep 5;247(5-6):280–92. doi:10.1159/000541149.

Abu AM, Herbort CP, Tabbara KF. A clinical approach to the diagnosis of retinal vasculitis. International Ophthalmology. 2009 Feb 4;30(2):149–73. doi:10.1007/s10792-009-9301-3.